Banking on a better life

- Welfare rhetoric out of control

- Banking on a better retirement, now

- Multinational business or a strong public sector

- TAI in the media

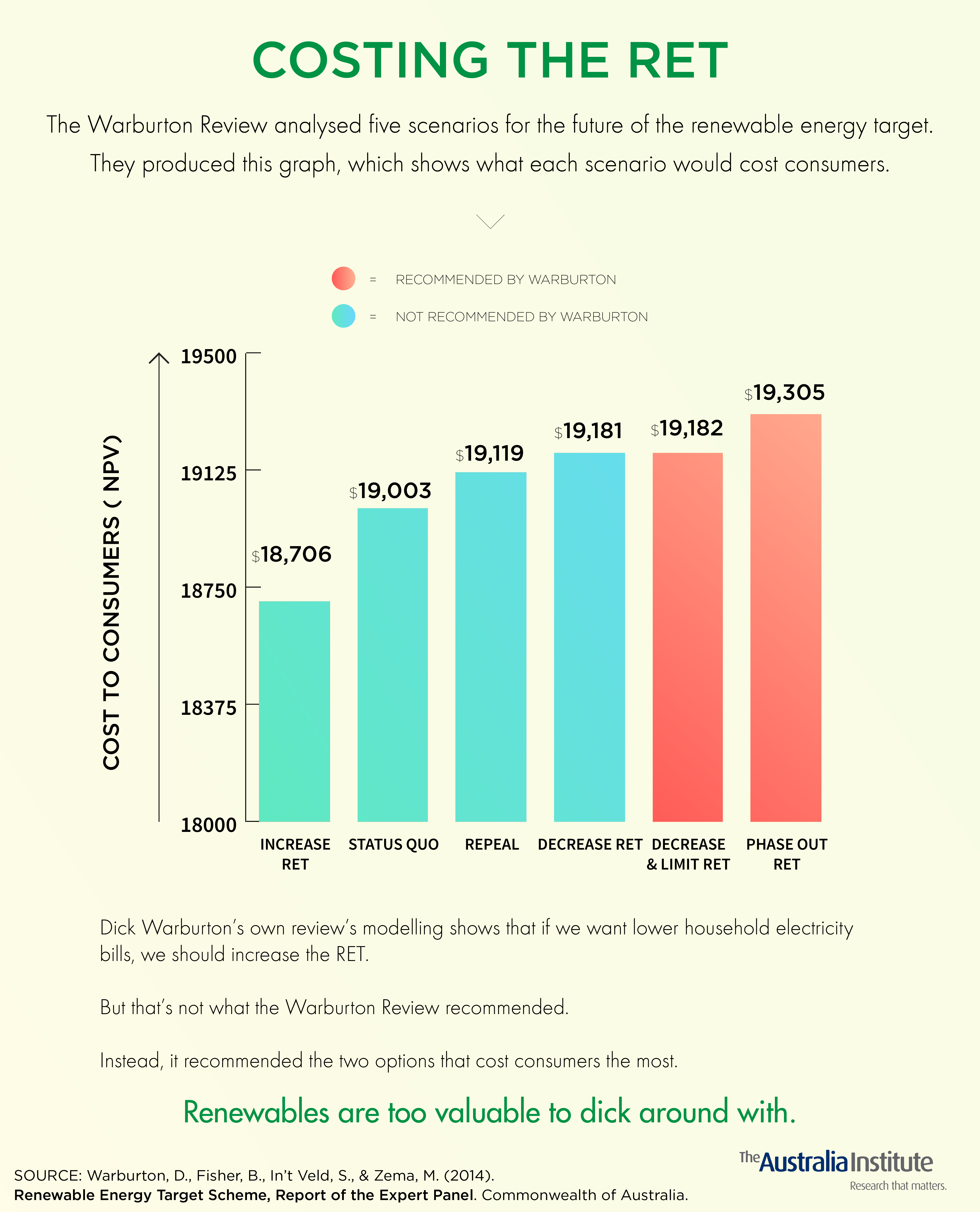

- Infographic

Welfare rhetoric out of control

Changes to the welfare system were due to be debated in the Senate this week. The controversial measures include the plan to make people under 30 wait six months for welfare payments, changes to the pension age and indexation and changes to family tax benefit B.

For these measures to successfully pass through the senate, the government will need the support of the crossbench and opposition. Clive Palmer has stated this week that he is “against everything” and “will be voting negative to the lot” whilst Labor say they will support “sensible reform”. As negotiations are occurring in the senate, it is worth examining the government’s arguments behind the reform.

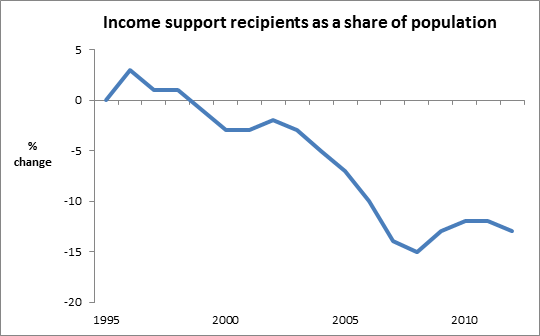

Much of the government’s rhetoric on welfare is that spending is out of control. Kevin Andrews has argued that it needs to be reined in, and that “the relentless growth in recipient numbers is not sustainable”. However, an examination of welfare benefit recipients shows that not only are the numbers under control, but they are actually decreasing.

The figure above illustrates the changes in welfare numbers between 1995 and 2012. The graph illustrates that welfare numbers have been steadily dropping since 1995, with a slight increase in the later years before it begins to drop again.

It is clear that the reality of welfare spending does not match the government’s rhetoric, and numbers are clearly not out of control. In a budget where we are all meant to do the ‘heavy lifting,’ the government is placing most of the responsibility upon those who are the least well off, leaving the wealthiest relatively unscathed.

Banking on a better retirement, now

Governments aren’t generally thought of as offering banking services, but they already offer a range of services that are, essentially, banking.

Higher education is probably the example that most people are aware of. Australia pioneered “income contingent” government loans that worked so well they took off around the world. But that is not an isolated example. There are many areas where governments act as a bank, they just try not to bring attention to this fact.

Another example, and one that is not nearly so well known, is the Pension Loans Scheme (PLS). Through this scheme, retirees can draw an income by borrowing from the government through a loan that is secured against property they own. As with other reverse mortgages, the loan is settled out of the borrower’s estate. But this reverse mortgage has a lower interest rate than you can get on the market.

The PLS is only available to rich retirees. If you get a pension, you can’t use it. You can only use it to bring your total payment from Centrelink up to the pension rate. The PLS has been around for 30 years but, perhaps due to its relative anonymity, no-one’s thought to ask why the government is willing to lend, but only to the wealthy.

Expanding the PLS would assist in a number of problems with retirement income policy. Unlike the $36 billion we will spend this year on superannuation tax concessions, expanding the PLS would help retirees now and need cost us nothing.

Centrelink currently excludes the family home from the pension assets test. This means someone in a very expensive house could be able to draw a pension.

But politicians don’t want to include the value of the family home in the asset test that stops people from getting a pension, because they don’t want to look like they are kicking pensioners out of their homes.

They don’t have to, if they extend and promote the PLS.

We often hear about how little the pension is and how hard it is to live on. But we also hear about how we can’t afford to increase it. Expanding the PLS to all retirees would allow pensioners to boost their own incomes at no cost to the budget.

We couldn’t find any detail on whether the PLS is subsidised, and to what level, but if the government wanted to it could easily make it cost neutral. Governments can borrow money more cheaply than the private sector. They already have huge databases on income, and interact with pensioners through Centrelink. These foundations make expanding the service pretty cheap.

If the government can be a better bank than the banks, why shouldn’t it?

Should we appease multinational business or fund a decent public sector? The international tax competitiveness index.

The 2014 international tax competitive index has just been published by the Tax Foundation which describes itself as a ‘non-partisan think tank’ based in Washington DC which was originally kicked off by a group of business executives concerned about the expansion in government revenue collections. It remains a sort of international beauty (or ugly?) competition for tax systems as decided by business.

The authors of the 2014 report summarises some of its key findings:

- The ITCI finds that Estonia has the most competitive tax system in the OECD. Estonia has a relatively low corporate tax rate at 21 percent, no double taxation on dividend income, a nearly flat 21 percent income tax rate, and a property tax that taxes only land (not buildings and structures).

- France has the least competitive tax system in the OECD. It has one of the highest corporate tax rates in the OECD at 34.4 percent, high property taxes that include an annual wealth tax, and high, progressive individual taxes that also apply to capital gains and dividend income.

- The ITCI finds that the United States has the 32nd most competitive tax system out of the 34 OECD member countries.

- The largest factors behind the United States’ score are that the U.S. has the highest corporate tax rate in the developed world and that it is one of the six remaining countries in the OECD with a worldwide system of taxation.

- The United States also scores poorly on property taxes due to its estate tax and poorly structured state and local property taxes.

In contrast to the above, Australia came in at fifth most competitive tax system overall but scored 24th for the corporate tax rate and 22nd for the international tax rules rank. The international tax rules rank is basically a measure of how well (badly if you are the business) the tax system brings your foreign dealings to account.

So what to make of all this—should we worry that we score below Estonia and be happy we are above the US and France? Taking just those countries Australia has slightly higher economic growth than top ranked Estonia, lower unemployment (6.2 v 8.5 per cent) but much higher living standards as measured by GDP per capita. Indeed, using a base of Australia = 100, Estonia is 52 while lowly ranked France and the US are 82 and 124 respectively. Hard to say much is going on there. On economic growth the US beats Australia but France is less. French and US unemployment is 11.0 and 6.4 per cent respectively. France like most of Europe is stuck in the aftermath of the global financial crisis but the US figure is roughly the same as Australian unemployment. The only difference is that Australia is increasing but the US is falling. All these figures come from the IMF forecasts for 2014.

All this suggests that there is not much to be gained from trying to beat Estonia to the top of the international tables. They might call it competitiveness but a lot of the countries at the bottom are better off than those at the top. Winning this competition is simply not worth it when a good healthy tax system is essential to fund health, education, infrastructure and the other public services vital to our social and economic system.

TAI in the media

Expand PLS to all age pensioners: TAI

‘Budget emergency’ denied by 63 leading Australian economists

WATCH our head of Research, Dave Baker, talking loneliness at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas

Listen Extended interview with Richard Denniss on ABC radio

Infographic

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

National Press Club Address – Yanis Varoufakis

Yanis Varoufakis addressed the National Press Club in Canberra on Wednesday 13 March, 2024.

Stage 3 Better – Revenue Summit 2023

Presented to the Australia Institute’s Revenue Summit 2023, Greg Jericho’s address, “Stage 3 Better” outlines an exciting opportunity for the government to gain electoral ground and deliver better, fairer tax cuts for more Australians.

Extract: Heat – Life and Death on a Scorched Planet by Jeff Goodell

When heat comes, it’s invisible.