by Richard Denniss

[Originally published on The Guardian Australia, 04 September 2019]

Are free markets more important than free speech? We aren’t supposed to ask such questions because each of those libertarian goals was supposed to reinforce the other. But they clearly don’t, so it’s time to take a closer look at what “freedom” really means in Australia today.

Alan Jones has been using his freedom to insult and disparage again. After telling his listeners that the then prime minister Julia Gillard’s father had “died of shame” back in 2012, and that she should be “tied in a chaff bag, taken to sea and dumped”, he recently urged Prime Minister Scott Morrison to “shove a sock down the throat” of the New Zealand prime minister, Jacinda Ardern, and to give her a “backhander” in another on-air rant.

But at the same time at least 80 advertisers have used their own freedom to withdraw their advertising from Jones’s Sydney radio program for fear of offending tens of millions of customers around the country. Fair enough, you might say. Jones is free to insult, and sponsors are free to look elsewhere. But not in the topsy-turvy land of Australian conservatives.

Andrew Bolt found it “chilling that corporate weaklings, spooked by largely anonymous trolls on social media, should connive at this closing down of debate by conservatives.” He was also concerned that “some advertisers buckled to a group that is actually so tiny that when it finally crawled out of the shadows and held a public rally in Sydney’s sunlight just 25 or so turned up, including invited speakers and rubberneckers.”

So, what’s all the fuss about? What do free marketeers, such as Bolt, have against companies making up their own minds about what is in the best interest of their customers and shareholders? If CEOs can’t be trusted to make such decisions, who do the free marketeers think should be?

If free market shock jocks don’t believe that CEOs can be trusted to deal with customer complaints or to make decisions about where to spend their advertising budget, what other areas might CEOs let their shareholders down in? Workplace safety? Paying fair wages? Protecting the environment? It’s a slippery slope.

And then there is the confusion about “virtue signalling”. As Gideon Rozner from the Institute of Public Affairs opined, “the lily-livered companies that pulled advertising from Jones’s show were within their commercial rights to do so, and would be far from the first big corporates to engage in such asinine virtue-signalling.”

But what’s wrong with virtue signalling? Should big companies signal their vice instead? Virtue signalling is at the heart of consumer capitalism. Indeed, what is branding if it’s not virtue signalling? Successful global brands literally make billions of dollars per year selling overpriced stuff by convincing people that displaying their brand signals something about the customers’ virtues. Perhaps the right of Australian politics wants to join forces with Naomi Klein in pursuit of No Logo?

Marketing and sponsorship dominate Australian public life. The big four banks spend more money on advertising than the Australian governmentspends on the entire ABC. At our Australian War Memorial, we thank the weapons manufacturers who sponsor the exhibits in a far bigger font than we use to remember those who gave their lives for our country. We stripped the names of athletes from our public stadiums and replaced them with the logo of the highest bidder and, at Jones’s urging, we even ran huge ads for a horse race on the sails of the Sydney Opera House.

Sponsors don’t only influence which sports, arts and community organisations will be well funded, they also influence which athletes, performers and, yes, which shock jocks, will be paid the highest salaries. So should anyone really be surprised that, when multiple sponsors choose to distance themselves from an individual or organisation, it has a big impact on revenues, profits and, ultimately, salaries?

The Commonwealth Bank, Coles, Volkswagen and Mercedes are among the 80 companies that have already distanced themselves from Jones, at an estimated cost to shareholders in 2GB of around $1m. Do the rightwingers who bemoan the “nanny state” and call endlessly for deregulation think we should draft new laws to stop profit-seeking companies from making decisions about their own advertising budget?

This isn’t the first time Jones has had sponsors walk away, but now that the high-profile Nine Entertainment is a major shareholder in 2GB, and now that social media makes brand scrutiny a much cheaper task, the old tactics of waiting for the storm to die down before things return to normal is unlikely to work.

Companies that have distanced themselves from Jones will presumably be asked by organisations such as Sleeping Giants and Mad Witches to make a long-run commitment to stay away until the controversial broadcaster makes a sincere and lasting commitment to change. And until such a commitment is made, shareholders in Nine Entertainment will know exactly how much Alan Jones’s freedom of speech is costing them.

There is no easy way to protect freedom. Laws that protect the absolute freedom of speech mean that people are free to vilify and intimidate others and laws that seek to protect individuals from being vilified and intimidated will inevitably impede freedom of speech. But if we aren’t going to use the law to protect people from threats and vilification, why shouldn’t people rely on their power as consumers and shareholders to make their preferences known?

Shouting fire in a crowded theatre isn’t a good use of free speech and neither is using violent language about how to treat women when, on average, one Australian woman dies at the hands of her partner every week. It’s hard to draft a law to capture common sense but it’s easy for consumers to switch retailers. Australia’s well-paid CEOs know that much.

• Richard Denniss is the chief economist at the Australia Institute

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

Truth, Lies and Consequences | Between the Lines

The Wrap with Richard Denniss While I have no doubt that the votes cast in the recent referendum were validly counted, I have major doubts about the arguments and evidence on which many of those votes were based. Misinformation and lies have always played a role in elections, but new technology has made it so

Bad Time for Corruption | Between the Lines

The Wrap with Richard Denniss After more than a decade of work, it was incredible to wake up on 1 July and know that Australia finally had a federal anti-corruption watchdog in place. The role of a think-tank is to make the radical seem reasonable, and one of the biggest challenges in explaining the impact

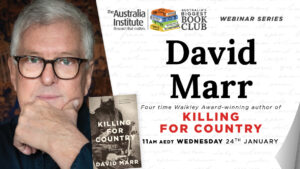

Extract: Killing For Country by David Marr

This is an extract from Killing for Country: A Family Story by David Marr, published by Black Inc Books.