by Richard Denniss

[Originally published on Guardian Australia, 05 February 2020]

If you think the quality of debate about climate change and bushfires is bad, allow me to give you a glimpse into the debate over the link between the supply and demand of fossil fuels and their price. Spoiler alert – according to the Morrison government, increasing the supply of gas pushes gas prices down but increasing the supply of coal doesn’t push coal prices down. Let’s unpack that.

First, we need to talk about “the law of supply and demand”. The vast majority of people – and the vast majority of politicians – have never studied economics, astrophysics or Chinese language. But while most people who haven’t studied Chinese or astrophysics wouldn’t try to teach other people Chinese or astrophysics, Australia is full of politicians and commentators who have never studied economics trying to teach people about economics. It never ends well.

The physical sciences have all sorts of “laws” like the “law of thermodynamics” and the “law of gravity” that explain things based on overwhelming empirical evidence. The law of gravity says that when you drop something it will fall towards the closest massive object. It’s straightforward and pretty reliable.

Economics has some laws too. But economic laws are a bit more like the guidelines for handing out sports grants – you can stick to them if you feel like it. According to the earliest chapters of the most basic economics textbooks, the law of supply and demand tells us that if you reduce the supply of something, then the price will go up. And if you increase the demand for something the price will go up, ceteris paribus.

But WTF does ceteris paribus mean?

Ceteris paribus is Latin for “all other things remaining unchanged” which is a pretty big caveat to stick on the end of a policy prediction. Consider the following:

If the supply of prawns increases then the price of prawns will fall, all other things remaining unchanged. But if something like Christmas happens in December, and people feel obliged to eat enormous amounts of prawns to celebrate the birth of Jesus, then the law of supply won’t help us make a useful prediction.

Think of “all other things remaining unchanged” as being similar to the terms and conditions on a car rental contract – easy to ignore, until you crash the car.

Ceteris paribus makes the impossible task of predicting the future seem simple by assuming that nothing unexpected will happen. It’s a useful thought experiment, but it’s no basis for real world prediction or real world policy making. For all of the scrutiny we’ve applied to the atmospheric models of climate change, it’s amazing that we let simplistic economic nonsense stand for so long.

No economist can say for sure what the future price of coal, gas, electricity or prawns will be. That said, economists can help us to have a sensible conversation about what is more likely to happen to the price of things, under likely circumstances.

So, let’s get back to why the prime minister thinks boosting the supply of gas will push gas prices down, but boosting the supply of coal won’t push coal prices down.

Over the last 10 years, gas production in the eastern states of Australia (overwhelmingly from Queensland) has increased gas production by around 300%. That’s a huge increase in supply which, all other things remaining unchanged, should result in a huge reduction in the price of gas. But – you guessed it – all other things aren’t at all equal.

Until 2014 gas produced in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia was never exported. But, in 2010 the Queensland government gave the green light to one of the largest and fastest expansions of unconventional gas anywhere in the world, allowing Origin, Santos and a group of global oil and gas giants to build three enormous gas export facilities, linking the Australian gas market to the world market.

As a result, it’s no longer the balance between the Australian demand for gas and the Australian supply of gas that sets the gas price. It’s now the balance between the world’s demand for Australia’s gas and the world’s supply of gas that sets the price. And, as the graph shows, the gas price for Australian consumers has tripled.

Scott Morrison knows that opening up more farmland around Narrabri for fracking won’t make gas cheap, that’s why he uses the weasel words of “downward pressure”. It is both true and meaningless. Just as a mosquito landing on a Boeing 747 places downward pressure on the plane, fracking at Narrabri will place downward, but irrelevant, pressure on the world price of gas.

While Australia is a big exporter of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), in the world energy market LNG, pipeline gas, and oil are all seen as substitutes and are all priced relative to each other. To put it bluntly, it’s simply BS to suggest that boosting gas production in NSW will lead to lower world prices for oil and gas. But it is true that, all other things equal, more fracking will put a mosquito’s worth of downward pressure on those prices.

When it comes to coal, the opposite is true. Australia has a bigger share of the traded coal market than Saudi Arabia has in the world oil market. While the decisions we make about gas have a negligible impact on the world price of gas, the decisions we make about coal have a major impact on the world price of coal. Everyone knows that if the Saudis were to double their oil production, the world price of oil would fall, but virtually every government in Australia pretends that if we succeed in doubling our coal production by opening up the Adani and other Galilee mines, it will have no impact on the world price of coal.

Morrison knows that opening up the Galilee basin would push down the world price of coal and, inevitably, that lower price would in turn increase world consumption of coal. But while he talks a lot about downward pressure on gas prices, he says nothing about what flooding the world market with more coal will do.

Australia is one of the richest countries in the world and we also have some of the world’s biggest coal, gas and renewable energy resources. We could have cheap energy, low emissions and low income taxes if we had managed our resources as well as the Saudis. But instead of restricting the supply of our scarce natural resources, we let foreign owned companies plunder them and they pay virtually nothing in tax for the privilege. It’s not too late to do something to fix this situation, but it’s a lot easier to blame “laws of supply and demand” or, better still, blame environmentalists, for the consequences of decades of policy failure.

Richard Denniss is chief economist at independent think-tank The Australia Institute @RDNS_TAI

Between the Lines Newsletter

The biggest stories and the best analysis from the team at the Australia Institute, delivered to your inbox every fortnight.

You might also like

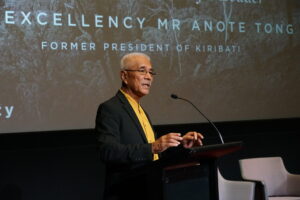

Navigating Australia & the Campaign to End Coal | Anote Tong

Climate change is the greatest moral challenge that humanity has ever had to face, and for those of us who have the capacity to stop it, are we going to do it?

Corporate Profits Must Take Hit to Save Workers

Historically high corporate profits must take a hit if workers are to claw back real wage losses from the inflationary crisis, according to new research from the Australia Institute’s Centre for Future Work.

Australia’s Climate of Discontent

Australia gives more aid to foreign fossil fuel companies than it does to our neighbours in the Pacific.